Sketchbooks, the Big Apple, John Brown, religion and graphic novels, and Salem witches: Author/Illustrator John Hendrix

Charlie Barshaw coordinates our regular Writer Spotlight feature and interviews writers of SCBWI-MI. In this piece, meet award-winning Author/Illustrator John Hendrix. John is also part of the cast of distinguished faculty at the SCBWI-MI spring conference.

You’ve been drawing your whole life, but it wasn’t until college that you realized you were an “Illustrator.” My wife Ruth, also an illustrator and sketchbook-keeper, had the same experience, someone putting a label on the thing maybe considered a quirk or odd obsession. How did knowing the doodles in your sketchbook were “illustrations” help you as an artist?

Actually those two revelations were very distinct moments in my career— in undergrad at the University of Kansas I realized that illustration as a category was an activity I had been doing my whole life. I just never really thought of what Norman Rockwell did as my calling.

I went to art school thinking superhero comics were the only way you could be a professional artist. Then after I spent my art school years learning to paint and to draw and to impersonate Chris Van Allsburg, I came to graduate school and realized that I hated sitting down to make art.

The act itself of painting was not nearly as fun as the act of drawing… and my sketchbook was the key to unlocking that realization.

Likewise, Ruth kept a sketchbook faithfully, but strove to do painterly picture book art. Eventually she would write and draw six “highly-illustrated middle grade novels,” the first one coming within a month of Jeff Kinney’s Wimpy Kid. Ellie McDoodle helped to invent the middle-grade graphic novel genre. But she thought all along that no one wanted her cartoony sketchbook stuff.

A sketchbook has the amazing ability to take what are simply raw and risky notions and turn them into a treasure map- simply through enjoyment. It is something I really articulated in my book Drawing is Magic where I tried to equate the act of drawing to the act of thinking. Keeping a Sketchbook is really just a way to transpose your best ideas into a visual form—as opposed to thinking of a sketchbook as a repository of perfect drawings…or even a collection of merely good drawings. In fact, bad drawings teach us so much more than perfect drawings, but no one likes to hear that.

Centering enjoyment as a methodology is really important. That doesn't mean the same thing as “following your bliss” or “chasing happiness.” Said another way, centering enjoyment means when you sit down to the drawing board you should really want to be there! What I realized was that enjoyment of a pen and a sheet of paper is what made me want to make things. I needed to do everything in my power to make that pure activity of drawing alone the central axis of my voice.

You were working in school working in a cramped painter’s style. But you came to realize the path to success was to do what you loved, so you embraced your sketchbook-style of drawing. Did this realization come as a “Eureka” moment, or did it come as numerous revelations?

In general I think “eureka moments” are overrated—yet I do have a very clear memory of a big turning point in graduate school. I was having a one-on-one review with Marshall Arisman who was the chair of my program at SVA, and he saw a drawing I had made where I fully intended to paint over the top of this drawing with gouache.

I remember very vividly Marshall seeing the ink drawing and telling me, “You need to put the brush down, this drawing is finished as is." It really made me look at what I was making in a different way. From that point on I began to see my drawings alone as ‘enough’ and not just that the drawing was only a preparation for making a “final” rendered painting.

Your first editorial art was in 2001 with the Village Voice. So, you had moved from Kansas U. to New York City. You weren’t yet working for the NY Times? What was your first apartment like? Did you take a “day” job? How did you land the gig with the counterculture Voice? In an interview you admitted the experience was less than satisfactory.

Ha, great research. Yes my very first freelance job was for the Village Voice in 2001 and the whole thing was a disaster from beginning to end. I had to do eight or nine sketches. The amazing art director Minh Uong was very gracious with me—basically handed me the entire concept for the image when I struggled to get there.

This was in the era before I was scanning art. So I was planning to deliver the final art in person, but it was November 12th, the day of the plane crash in the Rockaways. The subways were shut down, so I was freaking out that I couldn’t make it into the city from Jersey.

But… he gave me an extra day and I delivered the art and it ran and I was paid and I could move on! Lots of disaster in my first few months in the city.

My wife and I moved to New York just a few weeks before 9/11 and this project came in October of 2001 so the world was a strange place to be trying to make a living as an artist in New York City. This was two years before I got to the New York Times.

While I was in grad school I got an internship at the New York Times that eventually turned into a halftime position on the op-ed page as an art director. This allowed me to pay some of my bills while I began my freelance career.

Looking back it was really a ridiculous break. So many people spend their whole lives trying to work at the Times, and I fell into it almost by accident.

It was a wonderful job. I really miss it on some days. I think the best part was working with so many amazing artists and getting to know the illustration community from the side of the desk that commissions illustrations.

I got to work with Milton Glazer, Maurice Sendak, Jules Pfeiffer, Paula Scher, and so many other legends of the field. Not to mention collaboration with future stars that were getting their first jobs on the op-ed page like Jillian Tamaki, Yuko Shimizu, Sam Weber, Christioph Nieman, Tomer Hanuka.

The folks that mentored me at the Times I will never be able to fully repay, Steven Guarnaccia, Wes Bedrosian, Steven Heller, and Brian Rea.

Eventually you landed at the Times, and you’ve said much of your early work is for them. What was newspaper life back in the day?

I was at the New York Times for a few major news events that were really exciting: the blackout, the 2004 election to name a few. Sometimes I would just go down to the newsroom floor when a big story would break and watch the activity and commotion.

I always tell people that being an art director for the New York Times is like the extreme sport version of illustration because everything happens in about 4 to 5 hours and …it's really fun except when it's not and then you're scrambling to make a drawing for the page before it closes.

You’ve credited the NY Times job for your ability to network with other publications, as well as people in the book industry. Young and so naïve hick kid from Missouri in The Big Apple. (I see a memoire.) The question: How did young you navigate this big city hustle and bustle?

Yes, in some ways I was so naïve I didn't even know there was a wrong way to do promotion in New York. I think that innocence helped me on some level. I was just heartbreakingly earnest… I began to meet people and tried to become the biggest fan of the illustration industry.

Looking back I was really fortunate to be part of a community of young illustrators that included so many great friends with amazing talent. I was definitely scared of the city when I first got there but 6 months in you learn the ropes and after 4 years I thought we would be living in New York City for the rest of our lives but eventually we wound up back home in St. Louis Missouri.

You’ve done tons of periodical editorial work, covers and spot illustrations for articles back in the early days of this century. Print journalism is wheezing, on its last page. Do you still get editorial work from magazines?

Yes there's still a lot of commissions to be had in print editorial work believe it or not. I know that Time Magazine and Newsweek are not exactly selling 50,000 copies a week like they did in the old days but there are plenty of boutique publications and legacy news makers that still need a lot of custom artwork.

I do less than I used to mostly because I want to spend more time on my books but that's a wonderful privilege to be able to choose what I want to work on at this stage of my career.

You’ve won a slew of awards. Which one was most personally satisfying for you? Which was the most unusual recognition of excellence you’ve received?

I'm reluctant to talk about awards mostly because for the first 15 years of my career that's all I wanted out of my work. I've had to learn the hard way what healthy ambition looks like. Living for recognition is in some ways a folly of youth, and I know more today than I did when I was 25.

But, that said, there are a few awards that mean more to me than others. Anytime I can win a medal from the Society of Illustrators it is really moving. The jury is made of my peers and my heroes—so to receive their recognition means so much.

For the last 20 years I've dedicated much of my life teaching so when I won the Distinguished Educator in the Arts award last year from the Society of illustrators that was also extremely meaningful.

Honored to be on a list with my own MFA mentor Marshall Arisman, and other educators like Whitney Sherman, Murray Tinkleman and so many other legendary illustrator/educators.

In 2003 an art director from Scholastic saw a sketch of infamous John Brown in your portfolio. It had come from your thesis. What? Why’d you write a thesis on John Brown (whose body “lies moldering in the grave”)?

My MFA thesis was on the concept of “disaster” and so I did a kind of visual essay on how humanity interacts with tragedy. Of course this came out of my visceral experiences of 9/11 and processing what that meant to me and the world.

One image in that visual essay sequence was about John Brown whom I had been reading many books about at the time, and it eventually became my first authored picture book.

Much has been made of your choosing Mr. Brown as the topic of your book. He is, at best, a controversial figure in American history. So, after having done a picture book biography on one difficult subject, why not do an easy one? Not like — The Faithful Spy, about the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer. What drives you to tackle difficult subjects?

I think I like stories about the collision between high moral stakes, especially when religious faith intersects with the world at critical moments in history.

As I did a retrospective talk on my work a few years ago I realized that many of my books also orbit around the idea of fellowship and community and what we do with that—especially inside the church.

I think children don't get enough credit for being able to handle and understand complex moral dissonance. I write the kind of books that I wish I had read when I was 13 years old so …yes!

My authored works often involves complicated subjects that I need to make legible for young minds. I think of this as building ‘usable histories’ for readers. Not to mention that almost everyone dies at the end of my books

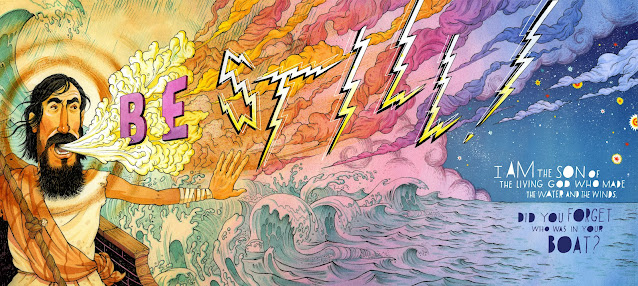

The NYT review of his 2016 book Miracle Man: The story of Jesus stated that “even nonbelievers will enjoy this powerfully told and visually dazzling book.” Unlike John Brown and Bonhoeffer, Jesus’ story is well-known. What made you think you could create something new? Did your doodling in church have anything to do with it?

I wanted to retell the story of Jesus as if it was a tall-tale or a folktale that you had never heard before. Part of the premise of the book is that Jesus's name is never said until the final spread.

My authored books fall into two categories: making the complex more legible, or "re-storying” something an audience thinks they already know. Miracle Man is a case of the second, of taking things that we know (or think we know) and decoding them and then re-coding them for a new audience.

My next project which is about the Salem Witch Trials is much more like Miracle Man than it is like The Faithful Spy in that almost everyone thinks they understand the story of Salem … but I'm going to try to recode it for them!

You also created a book about the Holy Ghost, and it’s a fun romp with a pious badger and a skeptical squirrel. How do you create a book on a religious topic without offending someone?

Well, the easy answer is to say you can't make a religious book without offending someone. The goal is not to limit offense. But I do really take seriously the responsibility of speaking about religious ideas.

I handle them with care. I'm sad to say that most of the people who criticize my books are fellow Christians. To be honest there is plenty of reason to disagree with someone theologically and I don't begrudge anyone who has a different interpretation of the Bible or scriptures, as long as it is done in “good faith.”

There are some that would interpret scripture to enrich themselves or gain power over others, and these are the ways of Jesus. But the premise of all art is to be able to see through the eyes of another—and in this case I'm not writing the book necessarily for other religious people!

In The Holy Ghost, I'm trying to express my own doubts and wonders about the claims of Christian faith. So in that sense the book is meant to be “art” and not “Dogma” or “Evangelism.”

You’ve created a number of graphic novel titles. Of all the genres, it seems the middle grade graphic novel is the most labor intensive to produce. How do you approach a graphic novel?

It's true graphic novels are just so much work. It's like being a one-man filmmaker. You are the person who is responsible for set design, costumes, lighting, screenplay, character design, cinematography, every detail of the story is totally up to you! The amount of choices you have to make can often lead to a kind of decision fatigue. I approach them slowly.

The Mythmakers for example took 5 years, including another year of reading and research. I try not to rush them and I try to enjoy the process as much as possible during the making and not reserve my enjoyment for the final product.

I believe it was Bob Dylan who was once asked, “what do you write first …the words or the music?” and he said, “Yes!” This is how I feel about creating graphic novels. They start as this stew of words and images and I wish the process was much more linear—but frankly it's always a mess from start to finish. Hopefully you come out on the other side with a book that makes sense to the reader.

If you want to write a book, be a teacher. You definitely practice what you preach. How long have you been teaching? What’s your favorite thing about working with students?

I've been teaching for 20 years and for the last 5 years I have been leading a graduate program called MFA Illustration and Visual Culture. I am the founding chair, but created it with other great faculty like D.B. Dowd, Shreyas R Krishnan, and Dan Zettwoch.

I love teaching for a lot of reasons but I think the experience of having a front row seat to see someone really come alive and find their voice as an artist is really satisfying.

I like the community of a school, which comprises faculty, students, and alumni, over many decades now. In a lot of ways I'm an accidental Professor. I didn't imagine that this would be my life's work… but the more I have done it the more I have realized that this is the best way I could have passed on any wisdom to the future.

If artists are honest with themselves they're all secretly working on their own “ immortality project.” The older you get you realize this is purely pride.

As artists, it is better to come to terms with the fact that we are all making sand castles…. but they are holy sandcastles! I find teaching to be one of the purest forms of loving one's neighbor.

You teach, write and illustrate books, do editorial art, record in your sketchbook, have a family, are active in the community and church. Often multiple of these in a day. How do you stay organized and focused and productive all the time?

This is a question I get asked about a lot and I often have no really good answer other than I feel pretty chaotic most days. I hope that can encourage you.

But I will give you some advice: Annie Dillard said this famously “the way we spend our days is the way we spend our lives.” If you're a perfectionist, it is tempting to feel like every task must be given 100% of your effort and this can often lead you to spending your days in ways you wish you didn't.

So, I think there is a thoughtful way to be strategically aloof. Choose where you will invest the greatest parts of yourself. Of course that may mean letting your email get longer than you wish or spending a little more time reading or writing than you had planned for.

Everyday I tried to make something… even the smallest drawing in my sketchbook counts!

Your home art studio was in the attic, then the basement. Where is it now?

Yes It is true. (I feel like you are stalking me.) We live in a house that was built in 1889 and I have an amazing attic with windows on four sides and wonderful light.

Inside my studio I have three or four different stations that I try to rotate around through the day— one for writing, one for her email, one for drawing Etc. This keeps me focused.

I do miss the studio I had in New York City. It was a wonderful studio in the Fashion District that I shared with Yuko Shimizu and Katie Yamasaki and I think about that studio to this day!

There is nothing better than an artistic community and though I love my home studio I miss the rich artistic fellowship of S.H.Y. Studio 2003-2005.

You intertwine text and images so that they’re almost a different art form. Art, you’ve said, should be expressive, but more important, communicative. How do you communicate when you marry picture and word on a page?

When people ask me to describe my work, specifically The Faithful Spy and The Mythmakers I often say that they are books made of 100% words and 100% pictures. And that's kind of a clever way to get around answering the question about how I think about the formatting of these books.

But truthfully, I design books for the way I like to learn things. And that is with a very blended synthetic language between images and maps and illustrations and comics and prose. The designing of these works is very challenging and it takes a ton of iteration to get it to make sense on the page.

You are a faculty member at the SCBWI-MI 2025 Spring Conference. What will you be teaching your students?

Here is a few of the topics I’ll be covering at the conference:

Type as Image: Don’t be Afraid to Draw Your Own Lettering

"How to Publish the Unpublishable"

Tales from pitching risky and unusual ideas.

A survey of advice about how to pitch your best ideas to editors and art directors.

"Drawing is Magic: Discovering Your Best Ideas in a Sketchbook"

For artists and writers, keeping a sketchbook can help hone your best impulses into clear ideas. Drawing games and group activities will demonstrate some key takeaways.

What’s on your drawing table now? What’s coming up that you’re excited about? Any long-range dreams?

I mentioned the Salem Witch Project book which is my next long-form graphic novel but the very next project that will be out in 2026 is a follow-up to my sketchbook Drawing is Magic and this new book is called 100 things: The list that Unlocks Your Best Ideas.

I've been really excited to revisit the content from Drawing is Magic since so much of my life is teaching young people how to draw and to make new ideas. Very excited to share this project with the world next year.

Please share any social media platforms:

Bluesky: @johnhendrix.bsky.social

Website: www.johnhendrix.com

BIO:

John Hendrix is a New York Times bestselling author and illustrator. His books include The Faithful Spy: Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the Plot to Kill Hitler, called a Best Book of 2018 by NPR, Drawing Is Magic: Discovering Yourself in a Sketchbook, The Holy Ghost: A Spirited Comic, Miracle Man: The Story of Jesus, and many others. His award-winning illustrations have also appeared on book jackets, newspapers, and magazines all over the world. His most recent graphic novel, The Mythmakers: The Remarkable Fellowship of J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis was named a Best Children’s Book of 2024 by The New York Times. John is the Kenneth E. Hudson Professor of Art and Chair of the MFA in Illustration and Visual Culture program at the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis.

Extra Interior Pages from Miracle Man: The Story of Jesus:

What an incredible and exciting career, John! Thank you to you and Charlie for sharing this insightful interview! What a gift it is that you are sharing your artwork and your learning with students! Congratulations on your remarkable work!

ReplyDeleteWow. What a creative life and interesting backstory. Looking forward to meeting you at the SCBWI-Michigan Spring Conference, John. Thank you, Charlie!

ReplyDelete