Charlie Barshaw coordinates our quarterly Writer Spotlight feature and interviews writers of SCBWI-MI. This month's writer is Ruth Behar.

Writer Spotlight: Ruth Behar Finds Herself

You were born in Havana, and your family emigrated to New York City when you were young. Learning the English language was difficult, especially since Spanish was primarily spoken in your home. Second-language students were shuttled to the “dumb class,” but you and your character Ruthie found a way to become “the smartest kid in the class.” Was it like throwing a person in deep water to teach them to swim?

The experience of being placed in the “dumb class” when we arrived in New York City was something I could never forget. That you could actually be penalized for speaking a different language seemed unjust to me even as a child. Learning to navigate a new language and a new culture is, indeed, like being thrown in deep water and figuring out how to swim. You’re drowning until you learn to keep your head above water. That’s what it’s like for most immigrants, who don’t have time to go to school. They learn English, as my parents did, by repeating words and phrases they hear at work, on TV, and on the street. But when you’re a kid, you want to learn English quickly so you can stand up for yourself in school. I remember how hard I studied until I was moved into a regular class. As happened to me, and as happens in Lucky Broken Girl, Ruthie becomes “the smartest kid in the class” because she’s had a year to think and read and study with a tutor. Though she suffers being stuck in bed, she improves her knowledge of English, math, and reading. Something good comes from something bad. Most important, she gains wisdom about life and death, learns to be compassionate toward others, and realizes she wants to be a writer and artist when she grows up.

Your life was changed irrevocably when your family was involved in a horrific car crash. Was anyone else injured in the accident?

Everyone suffered injuries in the accident. My father and brother needed stitches for wounds to their heads. My mother was scratched up from head to toe. My grandmother was so traumatized she had to take tranquilizers. I was asleep when the accident happened. I wasn’t able to brace myself and that may be why my leg fractured.

Your leg was fractured so severely that the doctors put you in a body cast in the hope that both of your legs would continue to grow at the same rate. The year you spent immobile changed your life. Can you explain?

After fleeing Cuba and starting a new life with my family, it was terrifying to suddenly not be able to move at all. What if another catastrophe struck? How would I get away? What would become of me? I had a great fear of abandonment, a huge sense of my vulnerability. I felt I had become a burden to my nomadic family and especially to my beautiful mother who had to take care of my needs while I was bedridden. That we all survived the experience was amazing. In the process, my life changed completely. I had been an active girl, always playing hopscotch. Afterwards I became a shy bookworm. I spent long periods alone, reading or daydreaming, as I had done when I was in bed for a year. My family worried about me; they thought I was too serious, too quiet. I was afraid to run, play sports, scared of breaking my leg again. I lived in my head and fantasized about one day being able to travel and have adventures—something I had longed for when I was immobile. That may be why I eventually became a cultural anthropologist.

Although Lucky Broken Girl is based on your life, the fiction allowed you to sculpt the details. Most importantly for the plot, you were able to introduce kind neighbor Chicho, who helps Ruthie to walk again through the magic of dance. After decades of writing anthropological facts, how did it feel to have your writing be constrained only by your imagination?

It was liberating and wildly exciting and healing to be constrained only by my imagination in writing Lucky Broken Girl. I had always heard about the power of fiction writers. It was only when I experienced it for myself that I finally understood the great magic that can be wielded by the pen. I had the power to embellish reality and make it sweeter than it had really been. I had the power to invent things that had never happened and make them seem utterly true. Words I wished had been said to me could be said at last and make my heart so happy.

You chose to go to Wesleyan University, even though your parents had a more traditional view of a young woman’s future in mind. Were you headstrong, or did you know in your soul that your future held more than raising a family?

I was headstrong and I also had a bit of faith I was going to do the things I dreamed of – write, travel, read a lot of books, and have a house of my own filled with books, art, and sunflowers.

I love the visual of a young freshman Ruth striding across campus grasping a guitar case, and adorned “in silky white blouses, wavy skirts, tall boots and wide-brimmed felt hats.” Had you found your identity in this new environment?

Thank you for reminding me of this! I love that visual too. Back then I was intensely into flamenco guitar and had spent a semester in Spain and had a very dramatic image of myself, nurtured by reading Lorca’s tragedies. I had found an identity I much preferred to the dutiful daughter I had been until then. I had left home and was on my way to becoming the educated and free-spirited woman I wanted to be.

You’ve had many mentors in your life, from the home-school tutor while you were bed-bound, to the Spanish couple in college, to the poet in Cuba, to the storied Dulce Maria Loynaz. Do you see yourself as especially blessed, or are you simply more aware and responsive to the influential people who touch your life?

Maybe I am always looking for teachers. I am restless and always trying to reinvent myself. Teachers have played a central role in my life since the days I was bed-bound to the present moment, when I’m trying to write fiction in my old age.

You despaired at writing poetry, met artist and poet Rolando Estevez, then edited a book of poetry and wrote the lyrical Everything I Kept. You’ve loved to read fiction while writing non-fiction, but broke through with the middle grade Lucky Broken Girl. Your character Ruthie would initially respond “I can’t” to challenges, but then do it. Is that your arc, too?

Now that you put it this way, I think the answer is yes. Everything is impossible until it’s possible.

As a young girl in a crowded New York walk-up apartment, you found your private space at the bottom of the long staircase. Now, after traveling the world, you make your home in Ann Arbor. How did Michigan become your home?

Michigan was a big surprise in my life. I came on a fellowship, married and pregnant with our son. I thought we’d be in Michigan for just three years. Then I was offered a job at the university in Ann Arbor and stayed and now it’s my home. But I’m always careful to say I’m not “from Michigan” but rather I live “in Michigan.” Even after more than thirty years in Michigan, I feel that people need to know I’m an immigrant in Michigan—an immigrant from Cuba and from New York.

In one of your blog posts, you describe the range of emotions that “Home” affords.

Home is that place to which you want to keep returning.

Home is that place to which you never again want to return.

Is home that complicated for you?

Yes, home is that complicated for me. Here I’m thinking of home as birth place and for me that is Cuba and it is complicated in that way – it’s a place I keep going back to, wanting to reclaim a home my family gave up, and it’s a place I sometimes think I should leave behind because it has caused so much sorrow to all of those who have left.

How fortuitous that you stumbled on a cultural anthropology class during your senior year. Luck or fate?

Maybe both? I was looking for an intellectual framework that could help me understand all the deep issues that were important to me – identity, belonging, and the search for home. I tried studying philosophy but was told I would never do well in that field because I lacked an analytical mind. I was devastated. Then I stumbled into a cultural anthropology class that questioned the universal truth of philosophy. The simple idea that there were a diversity of peoples and cultures in the world, with competing claims on the meaning of the truth, set me on my path as a traveler and writer.

You produced the documentary film Adio Kerida, and now your son has settled in New York as a filmmaker in his own right. How do you feel about the full circle of your life and his?

I think it’s a blessing that our lives are interconnected as mother and son and as thinkers and artists. He lives in New York where I grew up and I live in Ann Arbor where he was born. I look forward to the books he’s going to write and the films he’s going to make.

The accident changed your life. You still fear driving a car, and you found it difficult to trust your repaired leg for physical activity. Yet you’ve embraced dancing, especially salsa and cha-cha. What is it with dance that gives you such joy?

When I was growing up, there was dancing at parties, bar mitzvahs, and weddings. We were Cuban, after all! I was surrounded by lots of people who loved to dance. But after the accident I felt clumsy and was embarrassed to dance. When I was in my thirties, I finally began to do some dancing as part of an aerobics fitness class. That led me to take dance classes. I learned a Cuban style of line dancing called rueda de casino, which is so much fun, and learned the cha-cha, which had been a favorite dance of my parents. I also took up Argentine tango, which is filled with the saddest and most beautiful nostalgia. I adore the music of these dances and enjoy singing along to the lyrics as I dance. When you dance with a partner you have to communicate with each other without saying a word and that is magical. Being able to move around in space following the rhythm of the music is the closest I get to feeling like a pelican gliding over the sea waves.

You’ve mentioned in various interviews that you plan to keep mining your personal history for future children’s books. One was to be an account of your grandmother’s solo trip from Europe to Cuba, another a cousin’s emigration to the U.S. during the Castro revolution. What are you working on now?

I have just completed the book based on my grandmother’s solo trip from Europe to Cuba. It is an epistolary novel and tells the story of Esther, a Polish Jewish girl working with her father to make enough money to bring her four siblings, her mother, and her grandmother to Cuba in the late 1930s as conditions are worsening in Europe on the eve of the war. The story is an immigrant journey that takes place in an unusual setting, showing how penniless Jews searched for their America in Cuba at a time when the door to the United States was closed. I loved writing this novel in the form of letters and can’t wait to share it with kids. The book will be out in spring 2020 with Nancy Paulsen Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House. I am currently working on my first picture book, which is about a young girl’s love for a great-aunt who must leave her home by the sea.

Ruth Behar is an award-winning cultural anthropologist at the University of Michigan. Her published works include Translated Woman, Traveling Heavy and An Island Called Home.

She won the 2018 Pura Belpre Award for Lucky Broken Girl. (For her You Tube video about receiving the winning phone call, click HERE. For her website, click HERE and for her blog, HERE).

Charlie Barshaw, pictured here with his wife, also Ruth, is a member of the SCBWI-MI Advisory Committee, is a proud contributor to The Mitten, and occasionally revises his YA novel.

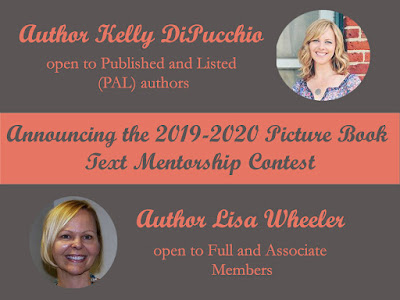

Coming up on the Mitten blog: Our new Ask the Editor feature, more tips for Painless Self-Promotion, and interviews with our two mentors for the upcoming 2019-2020 Picture Book Text Mentorship Competition.

Safe traveling for everyone headed to New York next week for the SCBWI Winter Conference, but first, it's almost time to register for our Marvelous Midwest Regional Conference! Registration opens tomorrow (Saturday, Feb. 2nd) at 9am. Don't delay, intensives and critiques will fill up fast! Go here everything you need to know, including registration tips.

Coming up on the Mitten blog: Our new Ask the Editor feature, more tips for Painless Self-Promotion, and interviews with our two mentors for the upcoming 2019-2020 Picture Book Text Mentorship Competition.

Safe traveling for everyone headed to New York next week for the SCBWI Winter Conference, but first, it's almost time to register for our Marvelous Midwest Regional Conference! Registration opens tomorrow (Saturday, Feb. 2nd) at 9am. Don't delay, intensives and critiques will fill up fast! Go here everything you need to know, including registration tips.

|

| Art by Dorothia Rohner |

Congratulations to you Ruth Behar!!! Can't wait to read your book.

ReplyDelete